A Question That Made Me Pause

While going through the Oxford interview question list, I came across a question that really caught my attention:

“If you could save either the rainforest or coral reefs, which would you choose?”

If I hadn’t studied corals in depth, I probably would’ve chosen the rainforest without much hesitation. But through writing my Extended Essay about coral bleaching, I realized how vital coral reefs truly are, and I found myself pausing for a long time in front of this question. After all, coral reefs cover only about 0.1% of the ocean’s surface. So why does the entire world grow so alarmed at their loss?

Image credit: Francesco Ungaro, Unsplash

The Mechanism of Coral Bleaching

Despite their still appearance, corals are actually animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria. This means they cannot produce energy on their own through photosynthesis or chemical reactions. Instead, they rely on symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae for nutrients, while providing these algae with shelter in return. They coexist through this delicate mutual relationship.

The exact mechanism behind coral bleaching is not yet fully understood. However, most hypotheses agree that when corals experience stress, they expel their symbiotic algae. Once deprived of these algae, corals can no longer receive nutrients and begin to weaken, eventually dying and turning white.

Image credit: Naja Bertolt Jensen, Unsplash

Why Is Coral Bleaching Such a Problem?

You might wonder, “If only corals die, why does it matter?” The truth is that although coral reefs occupy barely 1% of the ocean floor, they are estimated to host more than 30% of all marine species. In other words, their biodiversity is astonishingly high for such a small area. When corals die, the species that depend on them lose their habitats and food webs begin to collapse. Economically, coral reefs also hold enormous value as tourist destinations for activities like snorkeling and diving. The loss of reefs therefore harms both nature and humanity.

What Causes Coral Stress?

It might seem simple to say, “Then just make sure they don’t get stressed,” but coral stress can arise from many factors: higher temperatures, lower pH, and chemical pollutants among them. One of the most prominent and well-documented stressors is high temperature. According to Humanes et al. (2024), the mass bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016 was triggered by an 8 °C temperature rise, while similar large-scale bleaching in Palau between 1998 and 2010 occurred with sea surface temperatures increasing by about 7–8 °C.

The Need for Heat-Resistant Corals

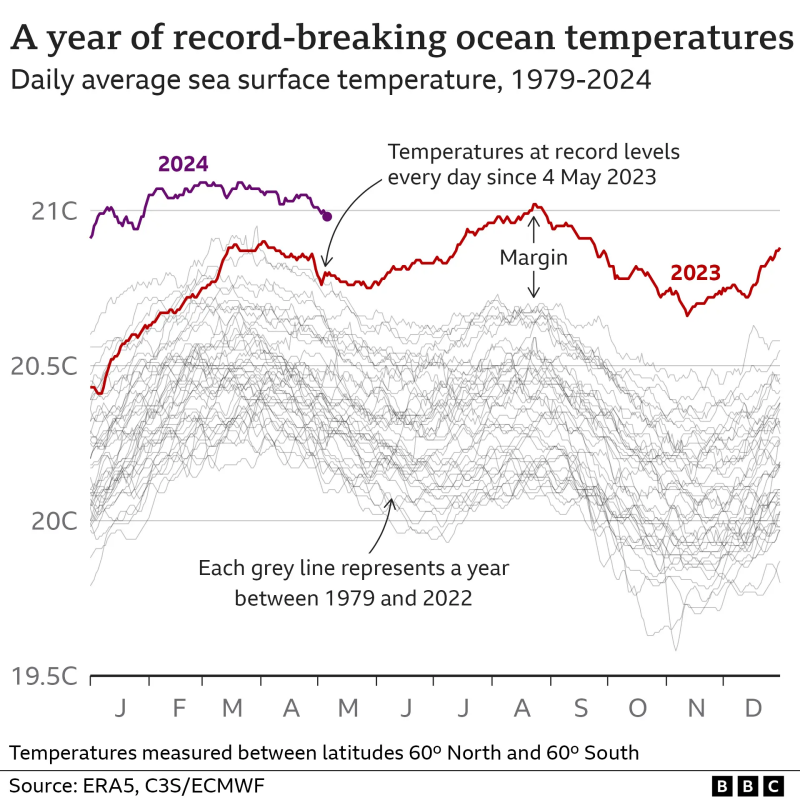

As mentioned earlier, corals exposed to heat tend to wither or die. Yet given the continuing rise in ocean temperatures, it is becoming nearly impossible to stop this trend. A graph in McGrath et al. (2024) shows that sea surface temperatures in 2024 and 2025 display patterns distinctly different from previous years.

The data, spanning from 1979 to 2024, reveal a sharp deviation between the red 2024 line and earlier gray curves. Temperatures in 2024 differ markedly even from 2023. This indicates that since 2023, ocean warming has entered a new phase.

Unfortunately, ocean warming is often reinforced by a positive feedback loop. As global and ocean temperatures rise, glaciers melt, reducing the reflective ice surface that bounces sunlight back into space. Less reflection means greater heat absorption, which in turn accelerates warming. This self-reinforcing cycle keeps pushing ocean temperatures upward.

Graph credit: McGrath M., Poynting M., & Rowlatt J. (2024, May 8). Climate change: World’s oceans suffer from record-breaking year of heat. BBC News.

CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Knockout Experiment (Cleves et al., 2020)

In 2020, Stanford University and AIMS collaborated on a CRISPR-Cas9 experiment that “knocked out” specific coral genes to investigate their roles in thermal tolerance.

The targeted gene in this study was HSF1 (Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1), known for regulating thermal stress responses in many organisms. When the HSF1 gene was knocked out and corals were exposed to 34 °C water, most of them died, while the unedited corals survived.

This experiment didn’t propose a new method but demonstrated a crucial insight: coral heat resistance is closely tied to genetics.

Assisted Evolution Experiment (Humanes et al., 2024)

Another recent study published in Nature in 2024 examined selective breeding as a method to enhance coral heat tolerance.

According to Naugle et al. (2024), even within the same coral species, some individuals exhibit higher thermal tolerance. Humanes et al. (2024) found that this tolerance can be inherited, with narrow-sense heritability (h²) estimated around 0.2–0.3. In other words, roughly 20–30% of coral heat resistance can be attributed to parental genetics.

Moreover, offspring from heat-tolerant parents showed significantly higher thermal tolerance, withstanding approximately +1 °C-week more accumulated heat stress (DHW) after a single generation of selection. However, long-term tolerance did not necessarily improve when only short-term heat-resistant corals were selected.

Conclusion

I understand the skepticism toward artificial intervention in nature and the anxiety about crossing a point of no return. Yet scientists continue to search for diverse strategies, such as PACE and other climate-resilience projects, to mitigate the crisis. Developing heat-resistant corals is one of those vital efforts.

As someone who deeply loves the ocean, I truly hope these beautiful reefs will remain with us for a long, long time.

References

Cleves P. A., Tinoco A. I., Bradford J., Perrin D., Bay L. K., & Pringle J. R. (2020). Reduced thermal tolerance in a coral carrying CRISPR-induced mutations in the gene for a heat-shock transcription factor. PNAS, 117(46), 28899–28905.

Hobman E. V., Mankad A., Carter L., & Ruttley C. (2022). Genetically engineered heat-resistant coral: An initial analysis of public opinion. PLOS ONE, 17(1), e0252739.

Humanes A. et al. (2024). Selective breeding enhances coral heat tolerance to marine heatwaves. Nature Communications, 15(1).

McGrath M., Poynting M., & Rowlatt J. (2024, May 8). Climate change: World’s oceans suffer from record-breaking year of heat. BBC News.

Naugle M. S. et al. (2024). Heat tolerance varies considerably within a reef-building coral species on the Great Barrier Reef. Communications Earth & Environment, 5(1).

Add comment

Comments